About Us

Our team was initially formed by Robert Xiao in February 2019 shortly after he took his position in the CS department. Robert started playing CTFs during his PhD with the top team PPP. Since then he’s competed in many high-tier CTFs including several DEF CON CTF finals, which is a classic “Attack/Defence” CTF that attracts many of the world’s most talented hackers.

Since our team’s formation, we’ve slowly attracted a core group of students and alumni that regularly play in CTF competitions. We very consistently play in a CTF each weekend, with exceptions around holidays and finals. Our mentality toward the competitions is usually casual, with a focus on learning and having fun, rather than competing. This means that there’s no obligation on any of our team members to regularly participate.

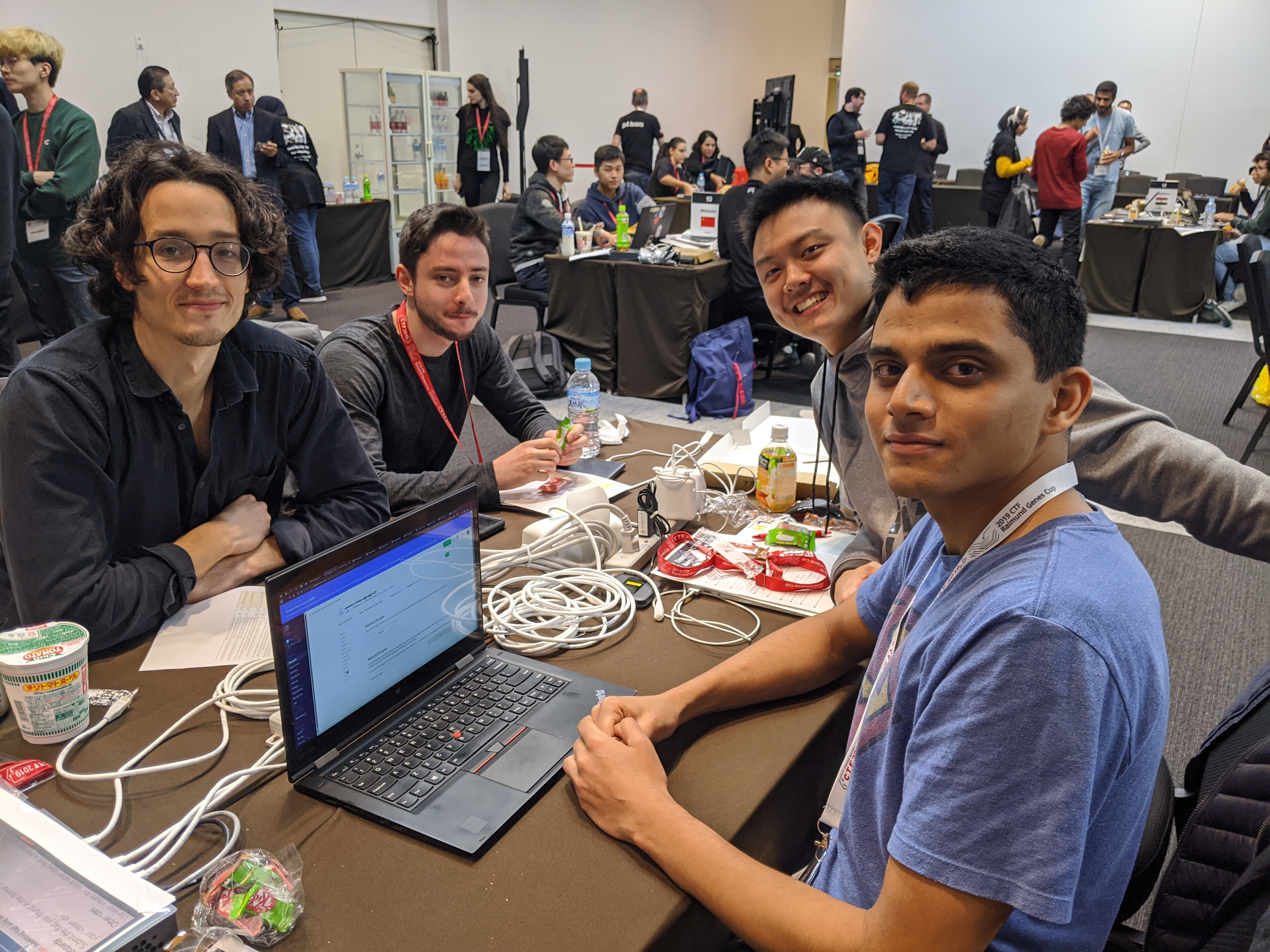

That being said, once we’re in the competition and racing for flags, we get pretty into it.

Our worldwide ranking and history can be found on ctftime.org. Some highlights are having won TamuCTF, b01lers CTF, and Cryptoverse CTF in 2022, winning b01lers CTF again in 2023, and having won DEF CON CTF in 2022 and 2023 in collaboration with PPP and The Duck as the Maple Mallard Magistrates.

We encourage any fellow UBC students, faculty or alumni to join in, no experience required. You can join our weekly meetings, ask questions, and introduce yourself if you wish. You may also join and participate in any CTF that we play together. We announce our plans to participate in upcoming CTFs on Discord.

Additionally, we host a competitive team for those who are more experienced with CTFs and looking to dedicate time toward honing their security skills. Check out the competitive page for more info!

Weekly Meetings

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, we held our weekly meetings virtually. We’ve continued to hold our Tuesday meetings online on our Discord but meet in-person on Fridays in ICICS 005.

Our meetings are laid back and informal. There are several ways one of our meetings might go:

- We just talk about stuff

- Someone talks about a particular topic they have some experience in while others listen and ask questions

- Someone asks about a particular problem from a past CTF that they couldn’t do, then we discuss and maybe someone can explain it

- Someone offers to demo a solution to a previous CTF challenge

- We discuss which CTFs we would like to play in the upcoming weeks

If you’re interested in the club, we highly recommend just listening into some meetings and especially joining in for some CTF events. The best way to learn is to try it out and ask questions.

There’s no obligation to keep attending meetings or participating in CTFs after you try it out. This means you don’t have to stress about adding extra work on top of your already busy school schedule.

CTF competitions

We regularly participate in CTF competitions all throughout the year. We competed in 20 CTFs in 2019, 45 in 2020, 56 in 2021 and 2022, and 40 in 2023.

Once we decide to play in a CTF, there is no obligation to any of our team members that they must play.

However, sometimes, some of us will decide to “try hard” at a particular CTF. This might be because the CTF has a particularly good reputation, or we’re trying to qualify for finals. In this case, those that agreed to come out and try hard will usually make time in their schedule and ensure that they can put in a solid effort. However even in that case, it’s still totally non-obligatory. First and foremost, we’re all here to learn and enjoy the process.

We typically participate in jeopardy style events. This means that the event has several categories of challenges. Within each category, there are usually several challenges of varying difficulty. This means that we as a team can easily split up the work. People can work on the categories they’re most interested in and the appropriate difficulty level for them.

Each challenge will have a “value” that is the number of points your team gets for solving it. Often the value of a challenge will be calculated dynamically based on how many teams have solved it.

Most CTFs place no restrictions on team sizes. This means that our whole club can collaborate together. Often there are far more challenges than we’re capable of solving, so at this time we have no issues with too many people.

However, some CTFs do have a team size restriction. Those that decide to take a spot on the smaller team might have more expectation upon them to show up and participate. We all make sure to clearly communicate our commitment level in such a situation to avoid disappointing the rest of the team.

There are typically between 300-1000 active teams competing during a reputable CTF.

They’re usually between 12-48 hours long, but there are many outliers. Some CTFs go on for 30 days or longer. This means you get plenty of time to crack the difficult challenges. As mentioned, there’s no obligation on anyone to be around for the whole CTF. We often come and go as fits our schedule, but as mentioned, often some of us will make time in our schedules to participate.

The event will always have some kind of dashboard for teams to view their progress and the current scoreboard.

Everyone on the team can see the dashboard from their computer. Everyone can see which challenges we’ve solved and which we haven’t. Typically we each select a problem that most interests us and notify the rest of the team what we’re working on (so we don’t overlap and accidently solve each other’s challenges). If we get bored of a particular problem or get too stuck, we often poke around at other challenges to see if there’s something more interesting. Again, we always make sure to check if someone is already working on something before starting on it. Sometimes we decide to collaborate on problems. But often we work solo then ask for help and second opinions from others if we get stuck.

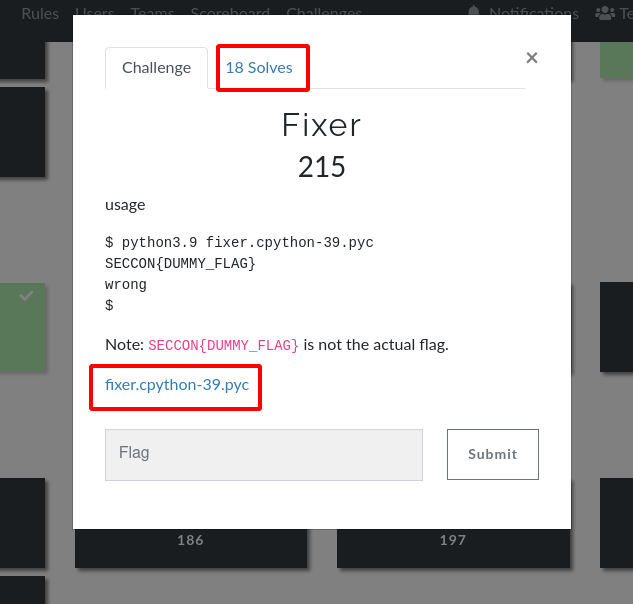

When you click on a challenge in the dashboard, it will typically display a short description of it, the number of teams that have already solved it, the number of points that challenge is worth and a link to download any associated files/materials. These files and materials will serve to help you work through the specified challenge.

Once you’ve mastered a challenge, you will be able to extract a “flag” from it, which you can submit into the dashboard and score our team some points!

A flag is a small bit of text, e.g., FLAG{ThiSiSaFlAG}. The specific way in which you recover a flag from a challenge varies significantly from challenge to challenge.

Challenge Categories

Binary Exploitation

Binary exploitation, also called “pwn”, can often be summarized as this: corrupt the memory of a running system to take control of it’s execution and gain access to the machine/server hosting it.

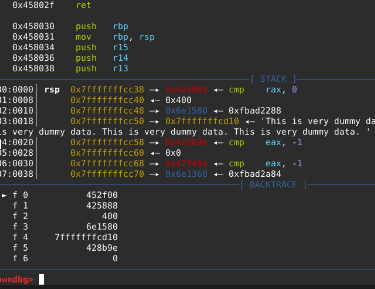

The typical structure is the CTF organizers would host a vulnerable program in the cloud and have it directly respond to incoming TCP connections. Your goal as the CTF player is to interact with the vulnerable program over the internet and figure out how to trigger a bug that gives you escalated privileges on the host machine running the program. Often we want to gain control over the CPU’s instruction pointer and redirect the program into executing something that lets us do stuff we’re not supposed to. Often once you get instruction pointer control, your goal would be to spawn a shell e.g., /bin/bash or /bin/sh (on linux systems) and direct the input/output of the shell program back to your computer. And with that, you get access to the remote machine, allowing you to retrieve the flag from it. Typically the flag will be stored in a file somewhere on the machine, e.g., /root/flag.txt.

The organizers will often, not always, give you a copy of the binary/binaries running on their server. This means you can usually analyze and study the system locally on your machine before firing off exploits at the real thing.

The first step with any binary exploitation challenge is to gather information about the system. This will vary significantly from challenge to challenge and depends if the organizers have given you a copy of the vulnerable code. In essence, you need to figure out what part of the system is vulnerable and what it’s vulnerable to. This is akin to reverse engineering.

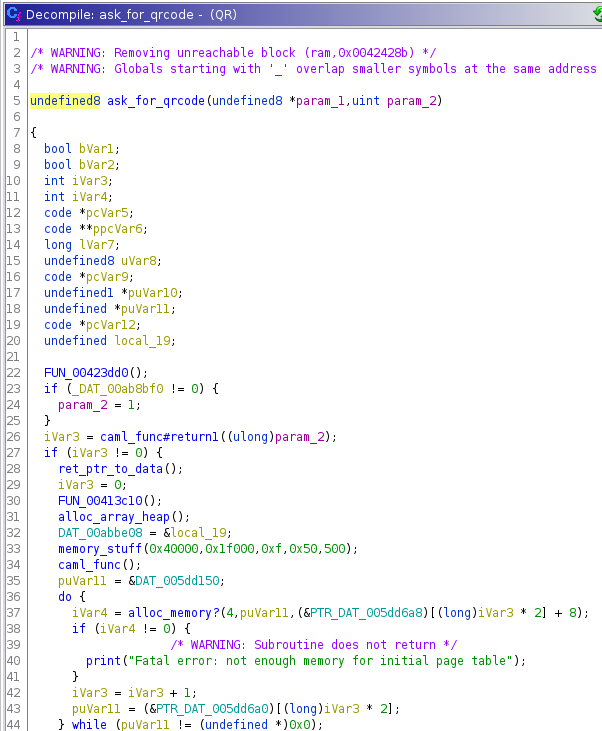

For information gathering, we often use a combination of “dynamic” and “static” analysis. For dynamic analysis, we’ll typically use tools like strace, ltrace, and gdb (with extensions like gef or pwndbg) to understand what the system is doing at runtime. For static analysis, we typically use ghidra, which can “decompile” many different kinds of machine code (e.g., intel, arm, mips, etc) into more human readable C code.

Once you’ve found and understood the vulnerability, your task is then to engineer a malicious “payload”, that you then send to the server. If you’ve correctly constructed the payload, it will trigger a bug or sequence of bugs on the server that give you escalated privileges on the server and allow you to retrieve the flag.

Reverse Engineering

Reverse engineering, can be summarized very generally as this: Given a complicated system, your goal is to sufficiently understand how it works such that you can “crack” it and extract the flag.

Reverse engineering is a crucial part of almost every CTF challenge. Every challenge has the initial barrier of first understanding the system you’re dealing with.

However, some challenges require more “reversing” than others. So much so, that jeopardy CTFs will almost always have a challenge category dedicated to just really tough reverse engineering tasks.

Reverse engineering is so general that it’s hard to provide an all encompassing example. However, it’s common that challenges in this category will involve reversing some kind of binary program. You would be provided with a binary. When you run the program, it might ask “What’s the flag?”. Then prompt you to enter the correct flag, e.g., flag{thisisaflag}. If you get it right, it might say “Correct!”, otherwise it might say “Wrong!”.

Now the goal is pretty obvious. You must figure out what the correct input is. Once you get it, you’ve got yourself a flag!

Figuring out what the correct input is can be very challenging. Often the systems are highly obfuscated, cluttered and the important logic is buried amongst a haystack of garbage. The art lies in combining your various dynamic and static analysis techniques to understand the inner workings as fast as possible.

It’s common for software companies to purposefully obfuscate the code they send to their customers in order to deter circumvention of their licensing mechanisms or protect their trade secrets. The reverse engineering CTF category stems from these real world issues.

Web Exploitation

Web Exploitation is the act of taking advantage of bugs in web applications, manipulating control flow between server and client, and analyzing numerous issues fundamental to the internet.

Web exploitation has many real-world examples, and so the nature of web exploit challenges in CTFs can vary widely. Oftentimes, they’ll follow patterns: abusing bugs to escalate user privileges, manipulating content to steal sensitive data from other users without them knowing, or accessing assumedly-private files from within an online server. The possibilities are endless, and the field of internet security is ever growing and changing.

Web exploit problems can encompass everything from XSS bugs to DNS exfiltration to SSL-cert spoofing - its likely that you’ll be learning a new type of exploit with each new CTF you participate in.

Each and every challenge present in this category share a fundamental paradigm - they are built upon a framework or foundation that was assumed to work one way, without understanding how they can work in other (unintended) ways. Many applications are made with one idea in mind - how a regular user would interact with it. However, what if a user does irregular things? What if they submit some input to an application that’s in a format the developer didn’t foresee? That is at the heart of web exploitation - manipulating programs to operate in ways it wasn’t meant to operate.

Cryptography

Cryptography literally translates to the art of writing ciphers and secret codes. It’s because of cryptography that we can send sensitive data over the web. In many cases, crypto is the brute powerhouse protecting most of our data online - our passwords, our banking information, anything involving the transmission of sensitive information. However, not everything is without its flaws, and cryptographic-related CTF challenges seek to showcase this - involving the breaking of popular encryption schemes that were not properly implemented.

Cryptography relies on the understanding of its base mathematical principles, which can be rigorous. But don’t be daunted by that - many challenges in the crypto category will utilize some piece of flawed logic that you can exploit to crack the encryption scheme wide open. It’s a matter of understanding the encryption rules in order to break them.

Cryptography is an immensely important function to our day-to-day internet lives, and this category seeks to ensure that the encryption schemes seeing widespread use are rigorously tested and correctly implemented.

Forensics

Forensics seeks to uncover the digital trail left behind by computer processes. Steganography, network packet capture analysis, and more all fall into this category. Forensics strengthens skills that examine and uncover hidden bits of information out of data files, uncovering secrets assumedly deleted or unattainable by normal means.

Forensics is a unique category involving clever manipulation of static file formats and unraveling hidden information. Think files-within-files, QR code reconstruction, or even reassembling corrupted files. Forensics will teach you where to find incriminating evidence in your filesystem and how to perform metadata analysis on the programs you are given.

Misc

Everything not under the five categories above will map to the Misc category. As such, the miscellaneous category is broad in scope and can touch on many different topics.

What category should I focus on?

Whichever one your heart desires! We don’t enforce any policy that would dictate what category you should develop skills in. Some people may find they like cryptography over binary exploits, or reverse engineering over web application security. We encourage everyone to explore and learn what they like, whether that be one or two specific categories, or an overall understanding of all categories.